Positioning stages today can satisfy specific and demanding output requirements. That’s because customized integration and the latest in motion programming now help stages get incredible accuracy and synchronization. What’s more, advances in mechanical parts and motors are helping OEMs plan for better multi-axis positioning-stage integration.

Mechanical advances for stages

Consider how traditional stage builds combine linear axes in X-Y-Z actuator combinations. In some (though not all) cases, such serial kinematic designs can be bulky and exhibit accumulated positioning errors. In contrast, integrated setups (whether they’re in the same Cartesian-stage format or other arrangements such as hexapods and Stewart platforms) output more accurate motion dictated by controller algorithms with no motion-error accumulation.

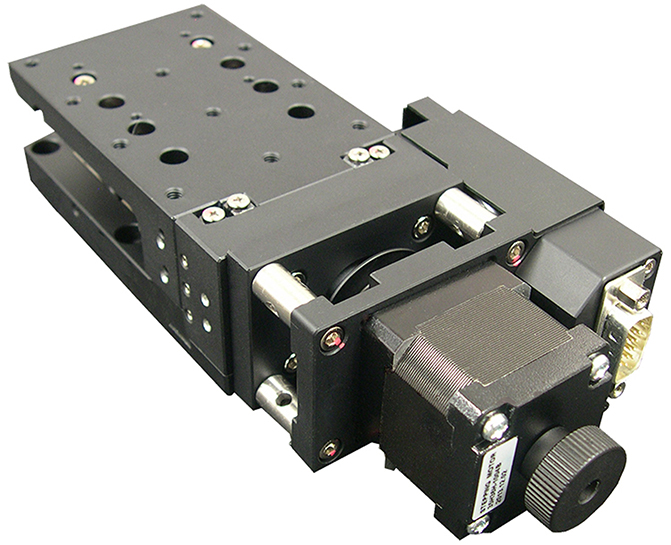

Case in point: Conventional screw-driven stages (with a motor and gearing on one stage end) are easy to implement when the payload doesn’t need its own power supply and overall length is a non-issue. Otherwise, gearing can go inside the stage at the motor end of travel, so only the motor length adds to the overall positioning-stage footprint.

Where needed, Cartesian setups can also minimize error when pre-integrated with specialty components—linear motors, for example. These are currently making big inroads in production machinery for high-speed packaging.

Some such subcomponents even come in forms that challenge traditional notions about stage morphology. “Curved linear-motor sections enable complete oval loops of power transmission. Here, guide wheels keep the moving element at precise distances away from the magnets for optimal force translation,” said Brian Burke, product manager at Bishop-Wisecarver. That’s a recent development. “Special wheel materials and bearing designs are necessary for the high acceleration rates—motion systems impossible only a few years ago.”

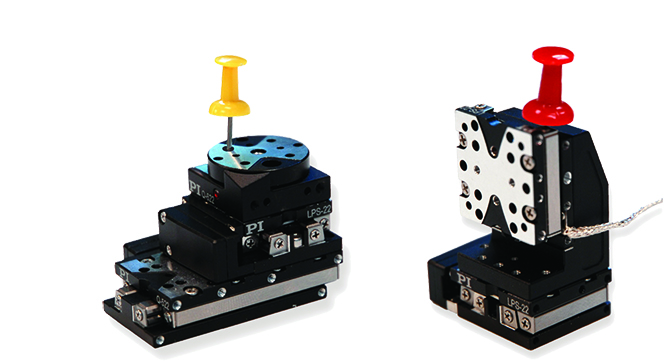

On smaller positioning stages, more accurate feedback devices, efficient motors and drives, and higher-performing bearings boost performance—especially in nanopositioning stages with integrated direct-drive motors, for example.

Elsewhere, custom versions of traditional rotary-to-linear components help keep costs down. Large-format applications can splice together servobelt stages without length limitation, according to Mike Everman, principal and chief technology officer at Bell Everman. Powering such long-stroke stages with linear motors can be too expensive, and powering them with screws or conventional belts can be challenging.

There is one caveat when picking between custom or commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) motion products.

“When deciding between a custom solution or an off-the-shelf design, it really comes down to application requirements. If an off-the-shelf solution is available and meets all application requirements, this is the obvious choice,” said Brian O’Connor, product manager at Aerotech. Typically, customized setups are more expensive but are exactly tailored to the application at hand.

Advances in positioning stages’ electronics

Electronics with low-noise feedback and better power amplifiers help boost positioning-stage performance, and control algorithms are improving positioning accuracy and throughput. In short, controls give engineers more options than ever for networking and correcting the motion of positioning-stage axes.

“The main advances in motion over the last decade have occurred in control systems and electronics,” said O’Connor. “Faster processors, state-of-the-art control algorithms, and more efficient electronics designs have enabled mechanical stage architectures that may have been impossible in the past.”

Consider how today’s packaging-line integrators don’t have time to build multi-axis functions from scratch. These engineers simply want robots that communicate and simple product flow through a series of workstations, according to Everman. In an increasing number of cases, the answer is special-purpose controls, partly because controls are far more economical than they were ten years ago.

Applications spur positioning-stage innovation

Several industries—semiconductor and electronics, medical, aerospace and defense, automotive, and machinery manufacturing—are spurring changes in today’s stages and gantries.

“All of these industries are driving change in one way or another,” said O’Connor. “In high-precision motion, we are being driven by industries trying to push yields and accuracies to levels that were unreachable just a few years ago. We realize that one size never fits all and rarely fits most.”

Although manufacturers deliver custom designs to all industries, high-tech industries (such as medical, semiconductor and data storage) are the ones pushing for more specialized stages. This is mainly from customers looking for competitive advantage.

Others see it a bit differently. “There is increasing need for small, high-precision motion components for applications in advanced research, life sciences and physics,” said Burke. However, he sees these industries are moving away from customized stages toward standardized products that are more readily available. “Small-footprint high-precision motion stages, such as the Miniature Precision (MP) series, are now available from Bishop-Wisecarver for demanding scientific applications,” said Burke.

“When an off-the-shelf solution gets you 90% of the way there, a custom solution has the potential to get you 100% of the way there,” said O’Connor. “In highly competitive industries, this extra 10% can mean the difference between being a lower-tier supplier versus a market leader.”

Large-scale industry moves to miniaturization have certainly driven some positioning-stage design to customization. The consumer electronics market is a driver in miniaturization, especially related to packaging in the form of thinner phones and thinner TVs, for example. “However, with those physically smaller devices come increased performance such as more storage and faster processors,” said O’Connor. Getting better performance here requires faster and more accurate automation stages.

“Silicon photonics and nanophotonics are areas with tremendous upside as well. Combining more devices onto a chip enhances the performance of the device,” added O’Connor.

However, device packaging and optical coupling requirements are well below a micrometer. “Coupling these tolerances with the throughput requirements of volume production creates a difficult automation challenge. In many of these cases, the stage or stages—or more importantly, the complete automation solution—must be custom to fit the exact needs of the end customer,” he explained.

IoT is making inroads in positioning-stage setups. In today’s connected world, consumers expect products to connect and work together. “In my mind, there is no doubt that IoT will reach all levels of motion control and factory automation,” said O’Connor. “Our products are well-equipped to support a connected factory. Whether that interconnectivity occurs via a PLC, fieldbus, wirelessly, Ethernet, or over drive analog-digital I/O, our drives and controllers offer solutions for factory connectivity,” he added. Future developments are in the works to further enhance this connectivity.

“As we collectively make progress toward the connected factory with higher levels of automation, the need to precisely monitor machine conditions will grow,” agreed Burke. Reliable, data-driven feedback of machine status has the potential to eliminate unpredicted machine failure.

IoT capabilities are already seeing use in semiconductor manufacturing and automation tasks that process expensive workpieces.

“Embedded sensors within linear bearings and guides will monitor changes in operating temperatures and additional vibrations, which are both leading indicators of bearing failure. By monitoring these parameters, at the bearing itself, corrective actions can trigger before failure,” said Burke.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.