Updated July 2016 || Accuracy is an important criteria in ball screw selection. But with two production methods and four different standards governing ball screw accuracy, making the best selection for your application can be a challenge. Understanding these standards and terminology, as well as the differences between the two manufacturing methods, will help you choose a ball screw that meets your specifications, without paying for higher accuracy than your application requires.

Defining the accuracies

The four standards that specify ball screw lead accuracy are JIS B1192, DIN 69051, ISO 3408, and ANSI-B5.48. The DIN and ISO standards are nearly identical and are sometimes referenced together (DIN 69051/ISO 3408 or simply DIN/ISO), while the ANSI standard is used less often than the others. Regardless of which standard(s) a ball screw manufacturer follows, they are all supported by the same underlying principle — how closely does the ball screw reach the intended position? To answer this question, the standards define four criteria for specifying ball screw accuracy.

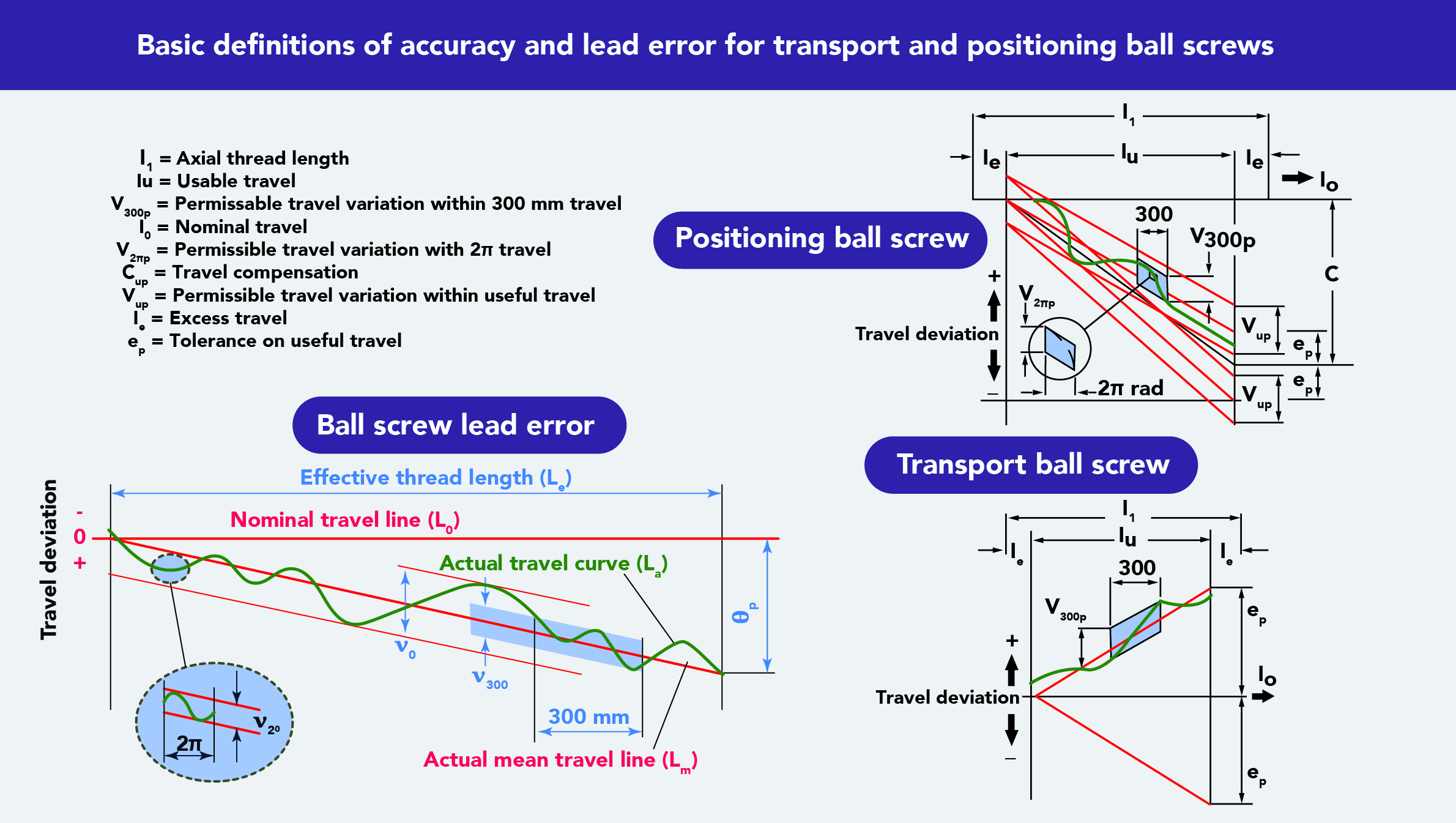

ep: Average lead deviation. The difference between the specified travel and the mean travel, where the mean travel is the best-fit line of the deviation curve over the useful length of the ball screw.

νu: Maximum deviation range. The maximum range of travel deviations (peak-to-valley) over the useful length of the ball screw. This is shown by two parallel lines which “enclose” the full lead deviation curve. (This specification is applicable only to positioning ball screws.)

ν300: Maximum deviation range over 300mm. This is similar to νu, but measured over any 300mm section of the useful length. The ν300 criteria is the most commonly used definition of lead accuracy.

ν2π: Maximum deviation range over one revolution (2πr), also known as “lead wobble.” (This specification is applicable only to positioning ball screws.)

While the DIN/ISO standards and the JIS standard are virtually identical for ep and ν2π specifications, they differ in the allowance for maximum range of travel deviation (νu) and maximum deviation over 300 mm (ν300).

Part of defining the intended purpose of a ballscrew is to determine whether it’s for positioning or load transport. For positioning screws, the maximum deviation range over 300mm (ν300) is not allowed to accumulate over the length of the screw. In contrast, it’s permissible for it to accumulate for transport screws. Maximum deviation range is most relevant to Grade 5 and (less often) grade 3 screws, because these grades can fall under either the positioning or transport designations.

I’ll take a “T,” please

The JIS, ISO, and DIN standards have categorized ball screws into two general groups: higher accuracy positioning ball screws, for applications such as machine tools, and relatively lower accuracy transport ball screws, for applications such as material handling. The JIS standard uses “C” to denote positioning screws and “Ct” for transport screws, while DIN and ISO use “P” and “T” designations.

To add further definition to the “positioning” or “transport” designations, a numerical accuracy grade is assigned. Positioning screws are graded on a scale of 0 to 5, and transport screws are graded as 7, 9, or 10. (Grades 0, 2, and 4 are defined in the JIS standard but not in the DIN/ISO standard.) In this grading scheme, lower numbers designate lower permissible deviations and therefore, higher accuracy. For example, a P1 ball screw has a higher accuracy than a P5 ball screw.

Beyond the intended purpose and accuracy, there is another reason to understand whether a ball screw is designated as a positioning screw or a transport screw. For positioning screws, the maximum deviation range over 300mm (ν300) is not permitted to accumulate over the length of the screw, while it is permitted to accumulate for transport screws. This is especially important for grade 5 and (less often) grade 3 screws, because these grades can fall under either the positioning or transport designations.

Precision means ground, right?

In short, no – at least not when discussing ball screw lead error and accuracy classes. Traditionally, it was assumed (and in most cases correct) that grinding was the only way to produce a positioning screw, due to the higher accuracy requirements. However, the rolling method for ball screws has been improved over the past two decades, and rolled screws can now be produced to meet the grade 5 and grade 3 positioning screw specifications.

To manufacture a rolled ball screw, a soft steel bar is passed through precision rolling dies to form the desired threads. It is then case hardened and cut to length, with the end journals being machined and ground in the final steps. The rolling method of ball screw manufacturing is generally faster and less costly than the grinding method.

The manufacturing process for a ground ball screw begins with a cut-to-length steel bar. The bar is first case hardened and the end journals are machined. Then the threads are ground, and the final step is finish grinding of the end journals. This order of operations allows the grinding steps to be completed using the same reference center, which can result in higher geometric tolerances, such as radial run-out and perpendicularity.

It is important to note, however, that geometric tolerances are also specified by DIN/ISO and JIS standards. Ball screws that are manufactured to these standards, regardless of whether they are rolled or ground, will not only meet the lead accuracy specifications explained above, but also the geometric specifications.

By understating that the manufacturing methods (grinding and rolling) are not synonymous with the “positioning” and “transporting” designations, and by choosing the ball screw lead error specification that best fits your application, you can avoid the risk and cost of using a screw that is higher accuracy than necessary or, conversely, that doesn’t meet your performance requirements.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.