Image credit: Thomson Industries

Power transmission screws—ball screws and lead screws—are typically used for converting rotary motion to linear motion. But when a load is applied axially to the nut, they do the opposite and convert linear motion to rotary motion. This is known as back driving, and is generally an unwanted effect. Although it can occur regardless of the screw’s orientation, back driving most often occurs in vertical applications when a load is stopped and the holding mechanism (typically a brake or counterweight) fails.

What determines whether a screw will back drive?

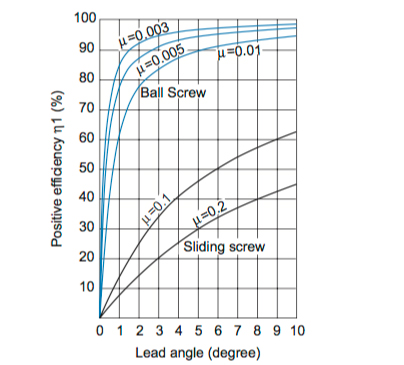

Efficiency is the primary indicator of whether a screw will back drive or not—the higher the efficiency, the more likely the screw is to back drive when an axial force is applied. Two main factors play a part in determining a screw’s efficiency: the lead angle of the screw and the amount of friction in the screw assembly,

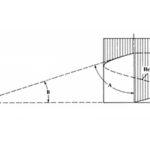

Lead angle—labeled “B” in the image below—is the angle between the helix of the screw thread and a line perpendicular to the axis of rotation.

The chart below shows that the larger the lead angle, the higher the screw efficiency. In other words, screws with a higher lead (20 mm vs. 5 mm, for example) have a higher efficiency and, therefore, are more likely to back drive.

Image credit: THK

Friction in a screw assembly comes from seals, end support bearings, and drag torque from the nut itself. Although seals aren’t typically used on lead screws, lead screws do have higher drag torque than ball screws due to the fact that they rely on sliding (rather than rolling) contact. This means lead screws often have lower efficiencies, and as a result, are less likely to back drive than ball screw assemblies.

When does back driving matter?

In vertical applications, most drive mechanisms—such as belts, rack and pinion drives, and linear motors—will let the load “crash” or fall if power is lost to the motor. Screws, on the other hand, are less likely to allow the load to drop, and if they do (that is, if the screw is back driven by the load), it will occur at a somewhat controlled rate, since the friction in the assembly, the lead angle, and the inefficiency of the screw all must be overcome.

Determining if a screw will back drive is relatively simple: compare the back driving torque to the friction in the screw assembly. Back driving torque is based on the axial load, the screw lead, and the screw’s efficiency.

![]()

Where:

Tb = back driving torque (Nm)

F = axial load (N)

P = screw lead (m)

η2 = reverse efficiency*

*Efficiency when back driving is typically less than the efficiency for normal operation. Be sure to check the manufacturer’s specification for the back driving efficiency.

To determine the friction in the screw assembly, add the friction torque of the nut, seals, and end bearings—all of which can usually be found in the screw manufacturer’s catalog specifications. If the back driving torque is lower than the friction torque of the assembly, the screw is unlikely to back drive.

A rule of thumb for lead screws: if the lead is less than one-third the diameter of the screw, the screw is not likely to back drive.

If the screws tolerance slop is back driven by a counterwieght system or function then when a drill bit or cutter begins to bite It can pull the backdriven slop to the other side and cause the bit to bite in farther than intended, which could cause the workpiece to be impacted loose and becomea projectile, or the bit or parts of the machine could break and become projectiles.. Therefore a counterwieght system of springs or wieghts or upsidedown mounting might be viewed with doubt.