In Part 1 of this post, we looked at various methods of driving the X axes in gantry systems and how the drive method can influence the gantry’s tendency to experience racking. Another factor that can cause racking in gantry systems is lack of mounting accuracy and parallelism between the two X axes.

Racking is the common name for a condition in which the parallel X axes in a gantry system don’t move in synchronization, causing the X and Y axes to lose orthogonality. Racking often results in binding of the X axes and potentially damaging forces to both the X and Y axes.

Any time two linear guides are mounted and operated in parallel, they require a certain tolerance in parallelism, flatness, and straightness to avoid overloading the bearings on one or both guides. In gantry systems, where the X axes tend to be spaced far apart (due to long travel on the Y axis), the mounting and parallelism of the X axes becomes even more critical, with angular errors being amplified over long distances.

Different guide technologies require varying levels of precision for parallelism, flatness and straightness. In gantry applications, the best linear guide technology for the parallel X axes is typically the one that offers the most “forgiveness” in mounting and alignment errors while still providing the required load capacity and stiffness.

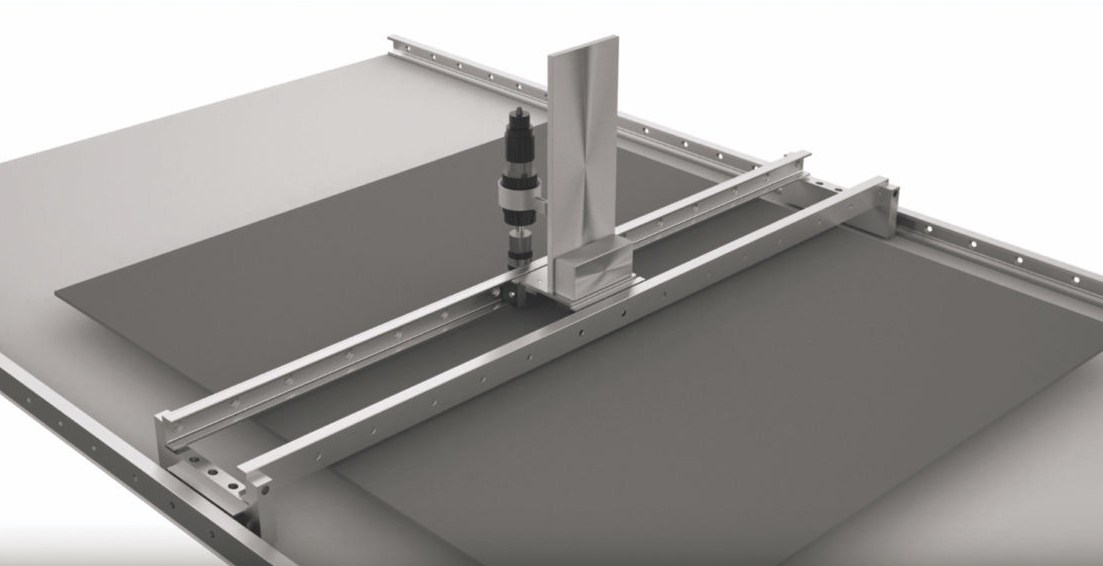

Image credit: Thomson Industries

Recirculating ball or roller profiled rail guides typically provide the highest load capacity and stiffness of all linear guide technologies, but when used in a parallel configuration, they require very precise mounting height and parallelism tolerances to avoid binding. Some manufacturers offer “self-aligning” versions of recirculating ball bearings that are able to compensate for some misalignment, although rigidity and load capacity may be reduced.

On the other hand, guide wheels that run on precision tracks require less accuracy in mounting and alignment than profiled rail guides. They can even be mounted to moderately inaccurate surfaces without causing running issues such as chattering and binding, even when two tracks are used in parallel.

Image credit: Bishop-Wisecarver

While alignment can be done with simple tools such as dial indicators and wires, the long lengths involved in gantry systems often make this impractical. In addition, aligning multiple parallel and perpendicular axes increases the complexity and required time and labor exponentially.

Image credit: Pinpoint Laser Systems

This is why a laser interferometer is often the best tool for ensuring straightness, flatness, and orthogonality between gantry axes.

Even if the design principles for linear guides and driving mechanisms discussed here and in Part 1 are followed, gantry systems that involve extreme lengths, speeds, or accuracy (or a combination of the three) may still experience racking. In these cases, mechanical devices such as pivots, slides, revolute joints, and spherical joints may be necessary to supply additional degrees of freedom and compensate for misalignment.

Danielle,

Nice treatment of a seldom discussed gantry problem.

Question: What methods or tools do you suggest or recommend for those of us who do not have, or do not have access to, a laser interferometer?